New York Violent Crime Arrests in 2021

by Vincent Liu

Introduction

In the United States, a few million people are arrested by police officers every year. The burden fell disproportionately on racial minorities, especially Blacks. In 2020, for example, out of 7.6 million people being arrested, around 2 million people were African Americans, which is equivalent to roughly 26 percent. However, the group represented only around 13 percent of the overall population. An overwhelming majority of these arrestees committed low-level, drug, and property offenses with less than 5 percent committing serious violent crimes. Evaluations of arrests returned mixed findings. On one hand, the practice puts criminals who may endanger society behind bars. On the other hand, it fosters irreversible negative socioeconomic impacts on people, which are disproportionately Blacks and Hispanics, low-income earners, homelessness, and individuals with serious mental illness.

This piece will take a look at arrests in New York, one of the most populous states in the nation, with an emphasis on arrests for violent crimes.

Effects and Impacts of Arrests

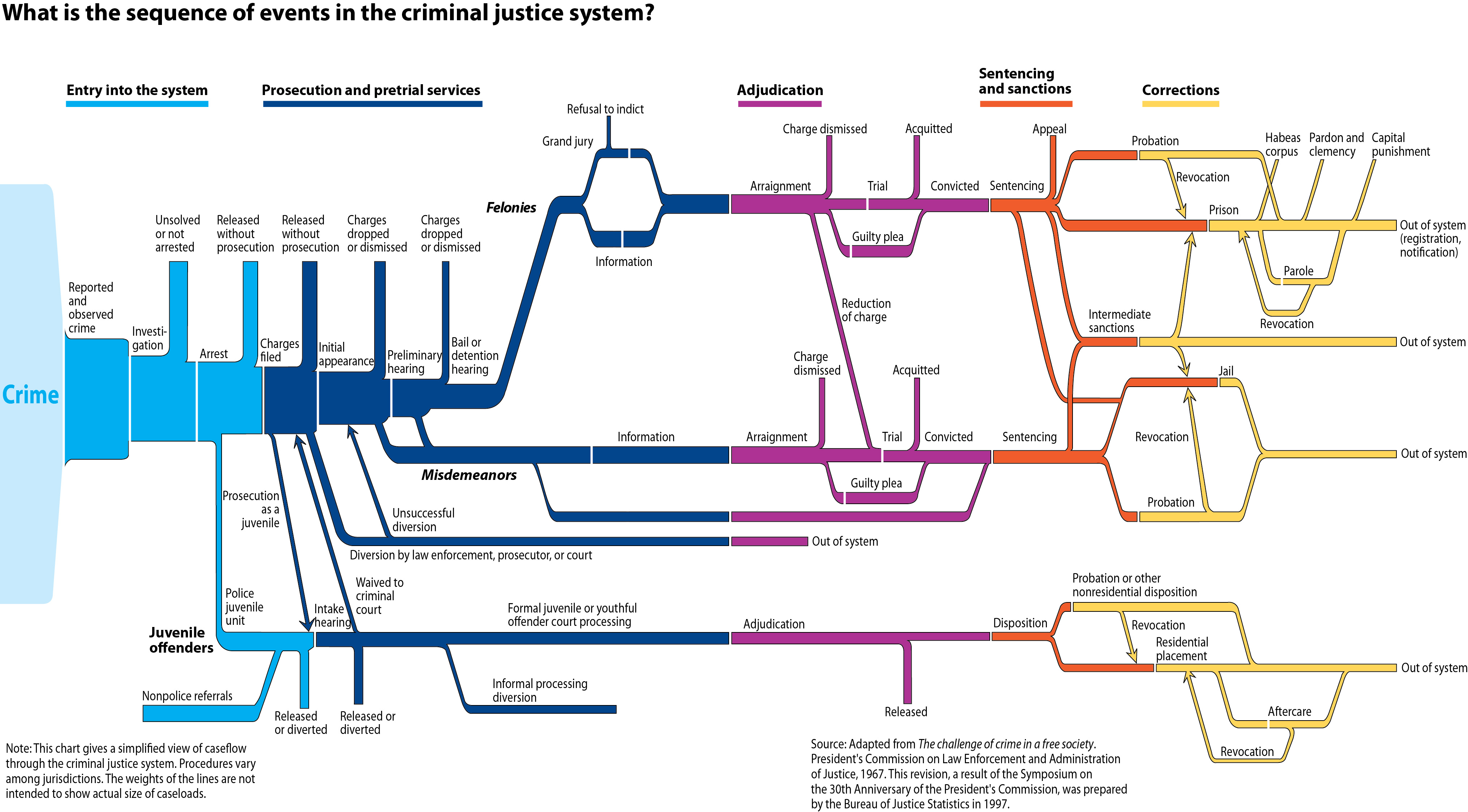

For most people, an arrest is their initial interaction with the criminal justice system and probably the only one they will have in their life. As illustrated by the criminal justice flow chart below, after being arrested, some arrestees are directly released, while others will further down the funnel, either having their case dropped at some points of the process or attending hearings and being charged. Arrests are naturally terrifying experiences, both physically and psychologically.

The practice serves important legal and policy meanings. For the Founders who wrote the lawbook of the criminal justice system, arrest is an important police power that can protect the rights of the majority when there is a conflict between personal liberty and public safety. For policymakers, arresting criminals is a popular crime control strategy that works through the deterrence effect - stopping crimes by increasing the cost.

However, the effect of arrest is often not as straightforward and positive as what political stakeholders have claimed. Little evidence suggested that arrests stop people from future wrongdoings. Coupled with other social phenomena, such as poverty and mental illness, the effects of arrests are profoundly negative on minorities and marginal populations, which account for the majority of people arrested. As the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) summarized in an infographic titled The Impacts of Arrest, the consequences of arrests are both long-term and averse. People with a record frequently face substantial barriers in the job markets, drop out of school at a greater rate, and suffer from chronic diseases. Arrest does not solve the problem of insufficient access to resources and support programs but instead, pushes people further down the line of making crimes by depriving their opportunities and causing the labeling effect. It is thus no wonder that the Prison Policy Initiative concluded that arrests usually leads to rearrests.

The Importance of Studying Violent Crime Arrests

The Federal Bureau of Investigations classified four types of offenses as violent crimes - murder, rape, aggravated assault, and robbery. As self-explained by the word “violent”, to validate a crime as a violent crime, two conditions are usually implied: the use of force and the infliction of great bodily harm. The word “force” does not necessarily suggest weapons and may simply refer to physical force, such as punches and strokes. For the latter, most harms are not advanced to the level of great bodily harm. The term itself usually requires the temporary or permanent loss of certain bodily functions or body parts, but the definition varies by state. Because of the multi-layer classification system of criminal offenses, it’s also important to note that the distincts between violent crimes and felonies. Any violent offenders are felons but the reverse may not be true.

Arrests for violent crimes are seldom studied by scholars and reported by journalists. Part of the reason is that as aforementioned, roughly 80 percent of arrests are for misdemeanors and low-level offenses. Compared to property and drug crimes, violent crimes are extremely rare and so do violent crime arrests. As an example, in 2019, roughly only 1 in 20 arrests is a violent crime arrest. Additionally, Violent crimes are also more often associated with gangs and other complicated issues, increasing the difficulty of studying the topic.

Whereas the challenges, violent crime arrests are an important part of law enforcement’s duty of protecting public safety because, in comparison to other offenders, violent criminals possess more risks to society and the consequence is more severe. More importantly, arrests do not work for misdemeanor offenders, but violent offenders are different. In New York, the state that my analysis focuses on, there have been clear associations between arrest rates and violent crime rates, which may indicate that arresting violent criminals could be an effective solution for stopping these crimes.

With visualizations below, I am hoping to answer questions about when violent crime arrests happened in 2021 in New York, which offense was more prevalent, if violent crimes are necessarily associated with the use of guns, and where New York was positioned among large cities in terms of its violent crime arrest rate.

Arrests for Violent Crimes were Concentrated in Summer. Blacks were Over-represented in Arrestees.

Very little study has given attention to the seasonality of arrests, however, this is an interesting angle to look at because criminal activities are often seasonal-people go out to the streets when the weather is warm and stay at home when the weather is cold. I noticed that in 2021, the number of violent crime arrests went up between February and June and fell between October and December. Summer was the season when NYPD officers arrested the most violent crime offenders.

Broken down by race, there wasn’t a significant difference between the number of arrests made on white and African American people in most months. However, considering whites are roughly four times the population of Blacks in New York, African Americans were over-represented among arrestees.

Last but not least, by looking at the trends of the three lines, it seemed that variations in the arrest numbers are mostly caused by changes in arrests of African American given fluctuations around violent arrest numbers of whites were milder comparatively.

How many violent arrests were made? When? Whom?

Source: 2021 FBI Uniform Crime Reporting System National Incident-Based Reporting System New York Arrest data

Aggravated Assault was the Most Common Violent Offense that Led to Arrests. Murder was the Rarest.

What violent crimes were committed? How many?

Source: 2021 FBI Uniform Crime Reporting System National Incident-Based Reporting System New York Arrest data

In 2021, 78 percent of violent crime arrests in New York were related to aggravated assaults, another 18 percent were related to robberies, and the rest was divided between rapes and murders. This is consistent with the overall picture of violent crimes nationally.

What deviates from the norm here is that rape and murder had roughly equal arrest numbers because the former is usually a few times larger than the latter. Associating findings from a Bloomberg study this year, which analyzed violent crime data in NY, that the murder rate was at its historical bottom point in the city, it’s more likely the rape number was the problem or that the rape was indeed at a low point in the city last year.

It should be noted that a lot of crimes are unreported to the police. The Pew Research Center compared crime statistics from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report and a self-reported survey administered by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, and found that only half of the aggravated assault cases and one-third of rape cases were reported to law enforcement in 2020. Either out of embarrassment, fears, or some other reasons, a lot of violent crimes are under the picture. This stays true regardless of the time and location.

Regardless of Race, Most Violent Crimes did not Involve any Weapon. However, Blacks were More Likely to Use a Gun than Other Racial Groups.

Americans have had complex emotions about guns that are divided among racial, partisan, and gender lines. As a 2021 Pew study found, over 70 percent of the US population believed that gun is an important problem faced in the nation. This sentiment is reinforced by a continuous surge in gun-related homicides in recent years and mass shootings that are constantly in the news. In spite of that, most violent crimes were not gun-relevant.

According to the chart, among all violent crime arrests made in NY in 2021, the majority of them (over 70 percent) did not have any weapons involved. In another 18-19 percent of cases, offenders used weapons other than guns, such as knives and stones. Finally, depending on the race, a gun or a rifle was involved in 4-8 percent of arrests.

The use of guns is yet race-dependent. Generally, Blacks were more likely to be arrested for gun-related violent crimes than other races (8 percent vs 4 percent). This may be related to the frequent activities of a few Black gangs in the state.

As journalist Jill Leovy wrote in her book Ghettoside, gun violence is a massacre against the same race as a result of failures in government regulations. Just because guns are not involved in most crimes doesn’t mean no actions should be taken to stop the gun violence epidemic.

Were violent crime arrests guns-relevant?

Source: 2021 FBI Uniform Crime Reporting System National Incident-Based Reporting System New York Arrest data

Last but not Least, among States that Had over 10 Million Populations in 2019, New York was on the Lower End of the Violent Crime Arrest Rate Spectrum.

Where is New York in terms of its arrest number?

Source: 2019 FBI Uniform Crime Reporting System report Table 69

The population estimates come from the US Census Bureau.

There are usually more crimes in big cities, where the population size and population density are higher. However, these numbers should be cautiously explained. A state with more crimes than another is not necessarily more dangerous because its population may be a few times bigger. When changing the scale from number to rate, a lot of findings also change.

When putting New York together with other states that are close to 10 million or bigger in size, New York was on the middle-lower to lower end of the violent crime rate continuum with 55 violent arrests being made per 10,000 people. On the highest and lowest ends of the spectrum are California with a violent crime arrest rate of 260 and Illinois with a rate of 4. Law enforcement in New York arrested more people per every 10,000 residents than Pennsylvania and fewer than Ohio. This roughly matches the violent crime numbers by state comparison.

Behind The Stories

Why Talking About Violent Arrests?

Arrests have been a huge deal in the lives of racial minorities in the US. Thousand of people are arrested for minor offenses and detained for their financial unaffordability. As a criminology scholar and student, I firsthand interacted with the incarceration system when working with a nonprofit in Minnesota doing the restorative justice practice. While talking with people, most of whom were charged with misdemeanors and some were felons in the last phase of their programs, they shared their pains, frustrations, and anxieties when being arrested. They told me that they were forced to wait in cold cells until being picked up by their relatives a few hours or days later who paid the bail on their behalf and that they didn’t know how to respond when their children asked about them. They told me they lost their jobs after their arrests and their families were also broken. They had nowhere to stay and they were lonely and regretful. They also told me that people began to look at them with different eyes, and these labels traumatized them, making them unapproachable. I think it was the volunteering experience I had that stimulated my interest in the issue of arrest and detentions. I also wrote these stories in an op-ed about Illinois’ new pretrial detention policy.

While doing research on the topic, I noticed that very few research focused on violent crime arrests. Studies about this topic were mostly completed in the last century and not with the intention of understanding the stories behind these arrests. This made me interested in conducting explorative data analysis with the data source I am already familiar with, which turned out to become this piece you are reading. Moreover, this one can also be considered a follow-up series of a data blogging trilogy I previously wrote for Towards AI on Medium about arrests in DC, which used the same database but with a different city focus.

Data, Data Limitations, and Data Collection

I used the 2021 National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) of the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) database for this project, which can be downloaded on UCR’s data exploration portal. UCR is a crime database system created by the FBI in the 1930s and has been tracking incident-level crime information ever since. Along with the aforementioned NCVS (National Crime Victimization Survey), the two systems are the nation’s primary and most official and authoritative crime measures. UCR represents a collection of over eight datasets among which NIBRS records state-based arrest information that is reported to the FBI in each available year, making it suitable for my topic.

UCR and every UCR-system database collect data from law enforcement agencies at different levels on a voluntary basis. This was not a problem when the program was first created early last century but with an only 85 percent reporting rate in 2020, this, unfortunately, became one of the major issues confronting the data system.

Another question about UCR is a common flaw of all official crime reports: a lot of crimes are not reported to the police. Especially for sensitive crimes like assaults and sexual assaults, many people were unwilling to tell officers what they experienced, making the statistics we see lower than their actual values. This issue may be adjusted by taking it into account in statistical modeling.

For the last chart, I also used the Census data besides UCR. To calculate the violent crime arrest rate, I did a data join on both datasets with the state as the common variable. Moreover, because I wasn’t able to find a 2021 estimate of violent crime arrest numbers in each state, I used the 2020 data instead. This may also lead to some biases.

For this project, I did all data wrangling using the software R, which I have been believing is superior to Python in data cleaning because of the usability of the tidyverse universe.

To see the whole data process, please go to my project Github page.

From Ideas to Charts

After deciding on the topic and data, I began thinking about what information to present. I think this is a two-step process. The first is to know what information is available to choose from in the data. The second is to select information. After data cleaning was done, my dataset remained with fewer than 10 variables including race, year, age, age group, month, sex, weapon, offense, and action taken by officers. The question then became the formula of what stories I want to tell and what information I want my readers to know and remember. Ultimately I decided to focus on four questions, which led me to pick four variables, race, month, weapon, and offense, and leave out the rest.

To present this information, I used four chart types: horizontal bar chart, vertical bar chart, line chart, and grouped pie (donut) chart. Horizontal and vertical bar charts are preferable to present (and compare) single-group information. Between these two, the former is superior when there are five or more groups and when group names are long. Although there are more complicated graphs I can use, I am a believer of complexity doesn’t mean better. I believe that to help readers grasp an understanding of which offense was the most common and comparing New York's violent crime arrest rates to other large states, bar charts, despite their simplicity, are the best choices.

I also used a line chart to present information about changes in violent arrest numbers over a time scale, which is often the best pick when at least one variable is time-related. To show the proportions of White and Black arrestees each month, I faceted the line chart by arrestee race. Alternatively, stacked vertical bar chars can serve similar purposes.

To showcase the proportions of weapon use in criminal arrest cases for each racial group, I used a small-grid/faceted pie (donut) chart, which can help readers see the breakdown of the information in different groups. Pie (donut) charts are often discouraged among policy researchers, however, after taking the class, I increasingly feel that the proper use of pie (donut) charts will add value to the whole rather than the opposite.

Last but not least, I added some interactivity components to promote user engagement. For two bar charts, when users hover over each bar, a text box with appear at the top-right side. For the line chart, users can highlight a line by hovering over it. For the pie chart, when users select a pie, the pie will become larger in size with shadow effects so that readers can see the area more clearly.

Challenges

For me, the biggest challenge was finding out how to modify chart details. This is my first time learning D3 and Javascript and these languages are so different from R and Python that many times, I was completely lost in terms of how to customize graphics as I desired. Some questions I encountered included, for example, how to remove x and y-axis lines, how to highlight a certain bar, how to change the color of a specific text, and how to apply tooltips to make my graphs interactive. I tackled each of them by googling, searching questions on StackOverFlows, and asking my professor, Tiffany, who never said no to my questions, despite some of them sounded like naive and stupid. I am very grateful for her patience and instructions.